There’s still a run on the real estate agencies, as toons corner the market on choice beachfront properties. In this installment, we cover the years 1951 through 1953 – another period when suntans seemed desirable in spite of dermatologists’ advice, while the salty ocean spray provided sufficient relative humidity levels to allow audiences to easy distinguishing the abundance of sand on the screen from the periodic run of foreign legion pictures.

Symphony in Slang (MGM, 6/16/51 – Tex Avery. dir.), deserves an honorable mention for purposes of this article. The film is an impressionistic marvel in compiling a seemingly never-ending assembly of visual puns on commomplace words and phrases, as a newcomer to the Pearly Gates kerflummoxes St. Peter and Daniel Webster with his modern turns-of-phrase in describing his life on Earth. Among one of the events in the young man’s life is a period where, dejected at rejection by his lady fair, he retreats to a South Sea isle and becomes “a beachcomber” – borrowing the old sight gag from Terrytoons’ Robinson Crusoe’s Broadcast to have him literally using a hair comb to sift through the beach sand. When the man’s story is concluded, Daniel Webster stammers for something to say, unable to comprehend a thing. The man sums up by asking, “What’s the matter? Has the cat got your tongue?” Webster embarrassedly looks off to one side, where an angel cat sits, holding just such a body part in its paw.

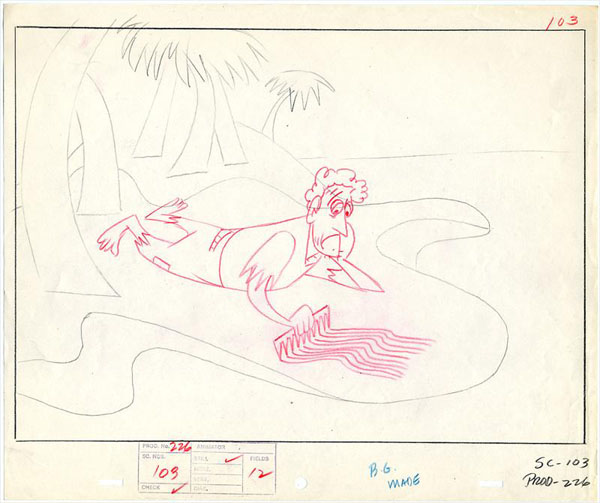

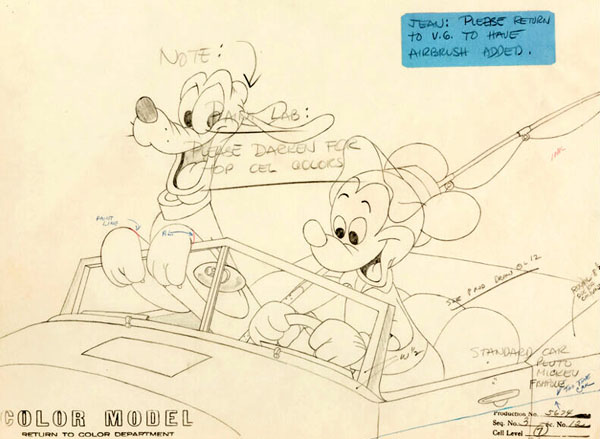

Original layout drawing from “Symphony In Slang” – courtesy of Howard Lowery Auctions

His Mouse Friday (MGM, Tom and Jerry, 7/7/51 – William Hanna/Joseph Barbera, dir.) – Roughly in the tradition of past Robinson Crusoe epics, Tom Cat is now cast as the adrift castaway aboard a raft. His food and water suplies empty, Tom turns to consuming a shoe (odd, in that he never usually wears one as part of his outfits), adding for additional calories the shoestring, as if ducking up a spaghetti noodle. He sights an upcoming island – but his destination is pretty much chosen for him by the ocean, as a wave picks up speed, and also the raft, then does a “Hawaiian Holiday” style transformation into a pair of watery hands, which bend the raft into a curve , then allow it to snap back into stright position, slapping Tom in the back, and driving him up onto the shore, then up the side of a cocoanut palm, and smack into the cocoanuts at its top. Tom tries to crack a cocoanut agaunst a rock. It merely rebounds into his face. Next, Tom spies a turtle as a passing meal – but appears to know nothing about the hardness of a turtle’s shell, chomping his teeth into it, and cracking most of them away.

His Mouse Friday (MGM, Tom and Jerry, 7/7/51 – William Hanna/Joseph Barbera, dir.) – Roughly in the tradition of past Robinson Crusoe epics, Tom Cat is now cast as the adrift castaway aboard a raft. His food and water suplies empty, Tom turns to consuming a shoe (odd, in that he never usually wears one as part of his outfits), adding for additional calories the shoestring, as if ducking up a spaghetti noodle. He sights an upcoming island – but his destination is pretty much chosen for him by the ocean, as a wave picks up speed, and also the raft, then does a “Hawaiian Holiday” style transformation into a pair of watery hands, which bend the raft into a curve , then allow it to snap back into stright position, slapping Tom in the back, and driving him up onto the shore, then up the side of a cocoanut palm, and smack into the cocoanuts at its top. Tom tries to crack a cocoanut agaunst a rock. It merely rebounds into his face. Next, Tom spies a turtle as a passing meal – but appears to know nothing about the hardness of a turtle’s shell, chomping his teeth into it, and cracking most of them away.

Enter Jerry, dressed in a miniature outfit and umbrella as if a little Robinson Crusoe. Tom sees him in three guises – as a walking pork ckop, chicken drumstick, and hot dog. As Jerry spots one of Tom’s paw prints in the sand, he steps backwards in apprehension. However, Tom is one move ahead of him, and has placed a frying pan in his path. As soon as Jerry steps in, Tom begins flipping him in the pan over an open fire. But Jerry lands on the handle instead, flipping the hot pan into Tom’s face. Tom pursues Jerry deeper into the island, then looks around, to discover he is in the middle of a seemingly deserted native village. To Tom, this doesn’t look good. Jerry adds to the foreboding, by beginning to pound out a savage beat from a tom tom drum. Tom rears backwards, catching his tail in the mouth of a large witch doctor’s mask. Tom turns to see it, screams, and backs up into the points of three spears resting against a hut. Jerry decides to really lay it on heavy, by approaching a cannibal cooking pot, and scooping up charcoal from its base to blacken himself up into the disguise of a miniature native. In one of his super-rare speaking appearances, Jerry now assumes a deep basso voice (provided by Paul Frees), and appears from the brush, bellowing out intimidating sounds that are a sort of native/English cross of nonsense words, including “Cocomo Ashtabula Yo Yo Azusa” and “Kalamazoo”, and a portion of which sounds like the mumblings of a tobacco auctioneer. At spearpoint, he drives Tom ino the cooking pot. Handing Tom a stack of vegetables, Jerry orders him, “Cutta potato”. Tom obliges, also cutting carrots as well. “Hold the onion”, adds Jerry, in the traditional cartoon gag. Jerry lights a fire under the pot, while Tom takes a moment out of his cutting to sample the broth in the pot around him with a ladle. Tom winces a bit at the taste, and adds salt to improve it, both in the pot and on himself. Jerry meanwhile is having a ball improvising a war dance. As he interpolates into it a few jutterbug moves, he fails to notice that the energy of his steps has loosened the grass skirt of his outfit, revealing his brown rear end where black should be. Tom catches sight of this, and approaches Jerry from behind, wearing Jerry’s grass skirt upon his own paw, and matching Jerry’s dance moves with the movements of his paw. As Jerry turns to observe this new “dancing partner”, he realizes the skirt is his own, and that his cover is blown. Adopring a sheepish grin, Jerry ad-libs a hasty exit, twirling a bone tied atop hs head to fashion it into a propeller for an airborne escape. Tom attempts to follow, but walks face to face into the cannibal villagers returning home. “Ummmm, barbecued cat”, announces their chief, smacking his lips. Tom flees in terror amidst a volley of spears. Jerry emerfes from the brush, happy to perceive the coast is clear. However, one additional straggler remains to be accounted for – a shorty of an islander, who pokes a spear into Jerry’s back, then smacks his lips with a comment of “Barbecued mouse.” And so, our heroes are both on the spit, with Jerry leading the little native off on another merry chase for the fade out.

Enter Jerry, dressed in a miniature outfit and umbrella as if a little Robinson Crusoe. Tom sees him in three guises – as a walking pork ckop, chicken drumstick, and hot dog. As Jerry spots one of Tom’s paw prints in the sand, he steps backwards in apprehension. However, Tom is one move ahead of him, and has placed a frying pan in his path. As soon as Jerry steps in, Tom begins flipping him in the pan over an open fire. But Jerry lands on the handle instead, flipping the hot pan into Tom’s face. Tom pursues Jerry deeper into the island, then looks around, to discover he is in the middle of a seemingly deserted native village. To Tom, this doesn’t look good. Jerry adds to the foreboding, by beginning to pound out a savage beat from a tom tom drum. Tom rears backwards, catching his tail in the mouth of a large witch doctor’s mask. Tom turns to see it, screams, and backs up into the points of three spears resting against a hut. Jerry decides to really lay it on heavy, by approaching a cannibal cooking pot, and scooping up charcoal from its base to blacken himself up into the disguise of a miniature native. In one of his super-rare speaking appearances, Jerry now assumes a deep basso voice (provided by Paul Frees), and appears from the brush, bellowing out intimidating sounds that are a sort of native/English cross of nonsense words, including “Cocomo Ashtabula Yo Yo Azusa” and “Kalamazoo”, and a portion of which sounds like the mumblings of a tobacco auctioneer. At spearpoint, he drives Tom ino the cooking pot. Handing Tom a stack of vegetables, Jerry orders him, “Cutta potato”. Tom obliges, also cutting carrots as well. “Hold the onion”, adds Jerry, in the traditional cartoon gag. Jerry lights a fire under the pot, while Tom takes a moment out of his cutting to sample the broth in the pot around him with a ladle. Tom winces a bit at the taste, and adds salt to improve it, both in the pot and on himself. Jerry meanwhile is having a ball improvising a war dance. As he interpolates into it a few jutterbug moves, he fails to notice that the energy of his steps has loosened the grass skirt of his outfit, revealing his brown rear end where black should be. Tom catches sight of this, and approaches Jerry from behind, wearing Jerry’s grass skirt upon his own paw, and matching Jerry’s dance moves with the movements of his paw. As Jerry turns to observe this new “dancing partner”, he realizes the skirt is his own, and that his cover is blown. Adopring a sheepish grin, Jerry ad-libs a hasty exit, twirling a bone tied atop hs head to fashion it into a propeller for an airborne escape. Tom attempts to follow, but walks face to face into the cannibal villagers returning home. “Ummmm, barbecued cat”, announces their chief, smacking his lips. Tom flees in terror amidst a volley of spears. Jerry emerfes from the brush, happy to perceive the coast is clear. However, one additional straggler remains to be accounted for – a shorty of an islander, who pokes a spear into Jerry’s back, then smacks his lips with a comment of “Barbecued mouse.” And so, our heroes are both on the spit, with Jerry leading the little native off on another merry chase for the fade out.

The Walrus and the Carpenter, an extended segment from Disney’s Alice in Wonderland (7/26/51 – Ward Kimball, sequence dir.), provides a sprightly vehicle for Kimball’s trademark zaniness. Veteran character actor J. Pat O’Malley appears to provide all the voices for the segment, including both the tutle characters and narrators Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum. Curiouser and curiouser, while this tale has beco,e associated with the vast majority of film adaptations of “Alice in Wonderland”, it is really an interpolation of material from “Through the Looking Glass”- just one of those favorite vignettes that directors seemed to love to get their hands on, in spite of the fact that “Looking Glass” itself has generally defied any literal intact translation to the screen. Its entire action takes place on a beachfront, and just below its watery surface, placing it squarely within the realm of this article series.

The Walrus and the Carpenter, an extended segment from Disney’s Alice in Wonderland (7/26/51 – Ward Kimball, sequence dir.), provides a sprightly vehicle for Kimball’s trademark zaniness. Veteran character actor J. Pat O’Malley appears to provide all the voices for the segment, including both the tutle characters and narrators Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum. Curiouser and curiouser, while this tale has beco,e associated with the vast majority of film adaptations of “Alice in Wonderland”, it is really an interpolation of material from “Through the Looking Glass”- just one of those favorite vignettes that directors seemed to love to get their hands on, in spite of the fact that “Looking Glass” itself has generally defied any literal intact translation to the screen. Its entire action takes place on a beachfront, and just below its watery surface, placing it squarely within the realm of this article series.

It should be noted that in actuality, this was the second sequence of the fim to take place on a beach. A shorter sequence precedes it, where Alice, trapped inside the room of locked doors while grown to giant proportions, begins to cry. Her tears are so large, they quickly flood the room. The talking doorknob, about to drown in the salty flow, points out to Alice the location of the bottle marked “Drink Me”, which Alice sips, instantly shrinking her to three inches high – and a perfect fit inside the bottle’s neck to sail on the sea she has created with her tears. Defying plausible size proportions, she and the bottle sail through the doorknob’s keyhole without using the key, then pass a variety of sea creatures, also floating on the waves, heading for a shore. As the bottle touches land, Alice observes the strange sight of Captain Dodo Bird conducting what he calls a “Caucus Race” a never-ending run in a circle around a high rock, which is supposed to dry off the participants after their long voyage. Never mind the fact that the rock is located directly in the path of the oncoming waves at high tide, so that Alice and the other creatures are getting drenched with every crashing splash, with only Dodo cozy and warm atop the pinnacle of the rock. Alice soon realizes the futility – and stupidity – of this activity, and instead diverts her attention to following the White Rabbit, who has also just washed up on shore. She follows him into the woods, but loses his trail. Instead, she finds two motionless twin figures, which she mistakes for statues – until they begin to speak. “If you think we’re wax works, you ought to pay, you know”, quips one. “Contrariwise, if you think we’re alive, you ought to speak to us”, chimes in the other. Thus begins the “beginning backwards” introductions of Tweedle Dum and Tweedle Dee, who, upon learning that Alice is “curious” about the White Rabbit’s activities and destination, react, “The oysters were curious, too, and you remember what happened to them.” With that lead-in line, Alice’s curiosity is temporarily redirected to what did happen to the oysters – and so, a tale within a tale is spun by the two roly-poly storytellers.

It should be noted that in actuality, this was the second sequence of the fim to take place on a beach. A shorter sequence precedes it, where Alice, trapped inside the room of locked doors while grown to giant proportions, begins to cry. Her tears are so large, they quickly flood the room. The talking doorknob, about to drown in the salty flow, points out to Alice the location of the bottle marked “Drink Me”, which Alice sips, instantly shrinking her to three inches high – and a perfect fit inside the bottle’s neck to sail on the sea she has created with her tears. Defying plausible size proportions, she and the bottle sail through the doorknob’s keyhole without using the key, then pass a variety of sea creatures, also floating on the waves, heading for a shore. As the bottle touches land, Alice observes the strange sight of Captain Dodo Bird conducting what he calls a “Caucus Race” a never-ending run in a circle around a high rock, which is supposed to dry off the participants after their long voyage. Never mind the fact that the rock is located directly in the path of the oncoming waves at high tide, so that Alice and the other creatures are getting drenched with every crashing splash, with only Dodo cozy and warm atop the pinnacle of the rock. Alice soon realizes the futility – and stupidity – of this activity, and instead diverts her attention to following the White Rabbit, who has also just washed up on shore. She follows him into the woods, but loses his trail. Instead, she finds two motionless twin figures, which she mistakes for statues – until they begin to speak. “If you think we’re wax works, you ought to pay, you know”, quips one. “Contrariwise, if you think we’re alive, you ought to speak to us”, chimes in the other. Thus begins the “beginning backwards” introductions of Tweedle Dum and Tweedle Dee, who, upon learning that Alice is “curious” about the White Rabbit’s activities and destination, react, “The oysters were curious, too, and you remember what happened to them.” With that lead-in line, Alice’s curiosity is temporarily redirected to what did happen to the oysters – and so, a tale within a tale is spun by the two roly-poly storytellers.

They tell of a day when the sun was shining with all its might – odd, because it was the middle of the night. The Tweedle brothers’ faces dissolve into the twin faces of the sun and moon, both up at the same time in a sky of half-light, half shadow, as below them on the beach trod a Walrus and a Carpenter. (This is Wonderland, after all – so no explanation whatsoever is offered as to how these disparate characters ever became fast friends.) The walrus wears a vest, suit, and reasonably formal hat – though there is a manner about him that suggests the formality is merely a put-on to cover the true character of a down on his luck ne’er do well – much in the manner of the outfit of Charlie Chaplin’s little tramp, or the studio’s own previous creation, J. Worthington Foulfellow Fox (aka Honest John). His true personality is further emphasized as he clandestinely scoops up a cigar butt from the sand with his walking cane, to allow the impression of him enjoying a polite smoke. The carpenter is definitely more professional in appearance, always wearing a working apron and hat, and having his tools at the ready. Still, given the company he keeps, and his present occupation of beachcombing, one can only surmise that even his business is not all it’s cracked up to be. As they meander down the shoreline, the Carpenter pauses, noticing something in his shoe. He removes and inverts the footwear, depositing on the beach a small mountain of sand four times larger than the shoe itself. With an industrious spirit, he proposes to the Walrus taking care of this constant bane to beachfront pedestrians, stating, “We’ll sweep this clear in half a year, if you don’t mind the work.” “Work?”, pipes up the Walrus. He hesitates and sputters, then resorts to what we discover is his favorite game of avoidance – changing the subject. “The time has come [the Walrus said] to talk of other things. Of shoes, and ships, and sealing wax. Of cabbages and kings”, quoting from the Lewis Carroll verse. It becomes evident he considers himself the more worldly-experienced of the two of them, and is determined to teach his younger friend “the ropes” of existence on the road of life – the first lesson of which is “No work today.” Prying the Carpenter out of the sand pile like a nail, using the back of the carpenter’s own hammer, the Walrus casually tosses the Capenter out of frame. The Carpenter lodges in a ledge overhanging the ocean floor. There, as he looks down into the water, he notices the surprising sight of a bed of oysters just below the surface. The oysters are of unique design. They each wear little pink nightshirts as they rest in the bottom half of their shells as if it were a cozy bed. Their upper shell is worn on their heads, resembling a little bonnet. Their feet consist of a pair of smaller shells – miraculous in their power to transport the oysters’ bodies, as they are neither connected at all to the bodies by either legs or feet. Upon being spotted, the oysters all duck out of sight, clamping down tight their top shells to their bottom ones. Much in the manner of Harpo Marx, the Carpenter signals with whisles and pantomime for the Walrus’s attention. Getting the message that a food find may have been discovered, the Walrus comes a-running. He offers a reaction of shock at seeing the Carpenter produce his hammer again, raising it as if about to pounce in attack on the oysters below. The Walrus pulls the Carpenter back with the end of his cane, them delivers a small bop with it upon the Carpenter’s head, signaling him in cautioning gesture as if to say, “No, no. That’s too uncouth.” Maintaining his dignity, the Walrus again pantomimes to the Carpenter as if to say “Watch me”, then wades directly into the ocean to demonstrate the manner in which a gentlemanly tramp obtains a free meal.

They tell of a day when the sun was shining with all its might – odd, because it was the middle of the night. The Tweedle brothers’ faces dissolve into the twin faces of the sun and moon, both up at the same time in a sky of half-light, half shadow, as below them on the beach trod a Walrus and a Carpenter. (This is Wonderland, after all – so no explanation whatsoever is offered as to how these disparate characters ever became fast friends.) The walrus wears a vest, suit, and reasonably formal hat – though there is a manner about him that suggests the formality is merely a put-on to cover the true character of a down on his luck ne’er do well – much in the manner of the outfit of Charlie Chaplin’s little tramp, or the studio’s own previous creation, J. Worthington Foulfellow Fox (aka Honest John). His true personality is further emphasized as he clandestinely scoops up a cigar butt from the sand with his walking cane, to allow the impression of him enjoying a polite smoke. The carpenter is definitely more professional in appearance, always wearing a working apron and hat, and having his tools at the ready. Still, given the company he keeps, and his present occupation of beachcombing, one can only surmise that even his business is not all it’s cracked up to be. As they meander down the shoreline, the Carpenter pauses, noticing something in his shoe. He removes and inverts the footwear, depositing on the beach a small mountain of sand four times larger than the shoe itself. With an industrious spirit, he proposes to the Walrus taking care of this constant bane to beachfront pedestrians, stating, “We’ll sweep this clear in half a year, if you don’t mind the work.” “Work?”, pipes up the Walrus. He hesitates and sputters, then resorts to what we discover is his favorite game of avoidance – changing the subject. “The time has come [the Walrus said] to talk of other things. Of shoes, and ships, and sealing wax. Of cabbages and kings”, quoting from the Lewis Carroll verse. It becomes evident he considers himself the more worldly-experienced of the two of them, and is determined to teach his younger friend “the ropes” of existence on the road of life – the first lesson of which is “No work today.” Prying the Carpenter out of the sand pile like a nail, using the back of the carpenter’s own hammer, the Walrus casually tosses the Capenter out of frame. The Carpenter lodges in a ledge overhanging the ocean floor. There, as he looks down into the water, he notices the surprising sight of a bed of oysters just below the surface. The oysters are of unique design. They each wear little pink nightshirts as they rest in the bottom half of their shells as if it were a cozy bed. Their upper shell is worn on their heads, resembling a little bonnet. Their feet consist of a pair of smaller shells – miraculous in their power to transport the oysters’ bodies, as they are neither connected at all to the bodies by either legs or feet. Upon being spotted, the oysters all duck out of sight, clamping down tight their top shells to their bottom ones. Much in the manner of Harpo Marx, the Carpenter signals with whisles and pantomime for the Walrus’s attention. Getting the message that a food find may have been discovered, the Walrus comes a-running. He offers a reaction of shock at seeing the Carpenter produce his hammer again, raising it as if about to pounce in attack on the oysters below. The Walrus pulls the Carpenter back with the end of his cane, them delivers a small bop with it upon the Carpenter’s head, signaling him in cautioning gesture as if to say, “No, no. That’s too uncouth.” Maintaining his dignity, the Walrus again pantomimes to the Carpenter as if to say “Watch me”, then wades directly into the ocean to demonstrate the manner in which a gentlemanly tramp obtains a free meal.

“Oysters, come and walk with us. The day is warm and bright. A pleasant walk, a pleasant talk, will be a sheer delight”, says the Walrus to the curious members of the oyster community, who cautiously peep out from their shells. The headstrong and more direct Carpenter pokes his head down into the water, and adds “And if we get hungry along the way, we’ll stop and have a bite!” With another bluster of mild frustration, the Walrus delivers several more blows with his cane upon the Carpenter’s head to knock some sense into him. Meanwhile, Mother Oyster, a larger specimen with a pearl added for a nose, observes a calendar hanging on a nearby rock, with the name of the month highlighting a flashing red “R” in it, and realizes they are indeed in season. She advises her brethren to stay where they are, safe in the sea. With another deft flick of his cane, the Walrus taps Mother Oyster’s shell to slam it shut, then falls back on his old change-the-subject rhyme once again, for which “The time has come” to lead the oysters onto land. Raising his cane to his lips in the motions of playing a Pied Piper’s pipe, the Walrus engages in melodic whistles, charming the rest of the oyster community away for a jaunty jig on the land above. As they climb into the dry air, and dance along over the shoals, the carpenter darts ahead, and busily plys his trade. Seizing up any stray piece of flotsam and debris he can find along the coastline (including an old rowboat hull, rudder, and fish monger’s sign), the Capenter works furiously to construct a makeshift hovel, as a fitting locale for the suggested stopover after a vigorous walk. Taking the cue, the walrus pipes his tasty followers into the shack, then shuts the front door.

“Oysters, come and walk with us. The day is warm and bright. A pleasant walk, a pleasant talk, will be a sheer delight”, says the Walrus to the curious members of the oyster community, who cautiously peep out from their shells. The headstrong and more direct Carpenter pokes his head down into the water, and adds “And if we get hungry along the way, we’ll stop and have a bite!” With another bluster of mild frustration, the Walrus delivers several more blows with his cane upon the Carpenter’s head to knock some sense into him. Meanwhile, Mother Oyster, a larger specimen with a pearl added for a nose, observes a calendar hanging on a nearby rock, with the name of the month highlighting a flashing red “R” in it, and realizes they are indeed in season. She advises her brethren to stay where they are, safe in the sea. With another deft flick of his cane, the Walrus taps Mother Oyster’s shell to slam it shut, then falls back on his old change-the-subject rhyme once again, for which “The time has come” to lead the oysters onto land. Raising his cane to his lips in the motions of playing a Pied Piper’s pipe, the Walrus engages in melodic whistles, charming the rest of the oyster community away for a jaunty jig on the land above. As they climb into the dry air, and dance along over the shoals, the carpenter darts ahead, and busily plys his trade. Seizing up any stray piece of flotsam and debris he can find along the coastline (including an old rowboat hull, rudder, and fish monger’s sign), the Capenter works furiously to construct a makeshift hovel, as a fitting locale for the suggested stopover after a vigorous walk. Taking the cue, the walrus pipes his tasty followers into the shack, then shuts the front door.

Inside, the Walrus and the oysters seat themselves around a small dining table with checkered tablecloth. The Carpenter joins them, with knife and fork at the ready. But there is skullduggery afoot, as the greedy Walrus prepares to engage in a double-cross. He suggests they begin with a loaf of bread, ushering the Carpenter away to the pantry to get some. The Walrus picks up a few of his invited guests in one hand, eyeing them as if about to chow down. But the Carpenter interrupts from the kitchen door, asking if pepper, salt, and vinegar might be in order. As anything will do to keep the Carpenter out of the way, the Walrus (after hiding the oysters in his hand) agrees that this would be a “splendid idea”. Once the Carpenter is safely occupied in the kitchen, obtaining the spices and preparing a special sauce, the Walrus tends to his dirty work. “And now…we’ll begin the feed!” “Feed?” cry the oysters, finally observing the menu that has been placed before the Walrus, with all standard entries appearing to read “Oyster Stew”,.topped with a daily special of oysters on the half shell. The Walrus scoops up the entire guest list of oysters into his arms, while the camera cuts away to the last preparations of the fixings for the feast by the Carpenter in the kitchen. Returning to the dining room and seating himself, the Carpenter looks around, and calls out, “Little oysters? Little oysters?” The Twedles provide the explanation for the silence which follows: “But answer there came none. And this was scarcely odd because – they’d been eaten, every one!” The Walrus sits alone, with incriminating swollen tummy, and a plate full of empty oyster shells. The Catpenter’s face turns beet red in hatred of his former comrade, and his hammer is again produced, now intended as a lethal weapon. The nervous Walrus rises from the table, retrieves his walking cane, and cannot finish more of his favorite phrase than “The time has come!”, then crashes through the front door in a hasty stage of retreat. The camera follows as the Carpenter pursues the Walrus at furious pace all the way back up the coast, hammer madly swinging, while the sun and moon morph back into Tweedle Dum and Tweedle Dee in time for them to conclude, “The End”. The story treatment elements fashioned by the Disney writers to embellish the original rhyme add zest and life to the characters and the tale, and certainly demonstrate more thought, planning, and effort in presentation than most competing versions of this story from other studios have ever approached.

Inside, the Walrus and the oysters seat themselves around a small dining table with checkered tablecloth. The Carpenter joins them, with knife and fork at the ready. But there is skullduggery afoot, as the greedy Walrus prepares to engage in a double-cross. He suggests they begin with a loaf of bread, ushering the Carpenter away to the pantry to get some. The Walrus picks up a few of his invited guests in one hand, eyeing them as if about to chow down. But the Carpenter interrupts from the kitchen door, asking if pepper, salt, and vinegar might be in order. As anything will do to keep the Carpenter out of the way, the Walrus (after hiding the oysters in his hand) agrees that this would be a “splendid idea”. Once the Carpenter is safely occupied in the kitchen, obtaining the spices and preparing a special sauce, the Walrus tends to his dirty work. “And now…we’ll begin the feed!” “Feed?” cry the oysters, finally observing the menu that has been placed before the Walrus, with all standard entries appearing to read “Oyster Stew”,.topped with a daily special of oysters on the half shell. The Walrus scoops up the entire guest list of oysters into his arms, while the camera cuts away to the last preparations of the fixings for the feast by the Carpenter in the kitchen. Returning to the dining room and seating himself, the Carpenter looks around, and calls out, “Little oysters? Little oysters?” The Twedles provide the explanation for the silence which follows: “But answer there came none. And this was scarcely odd because – they’d been eaten, every one!” The Walrus sits alone, with incriminating swollen tummy, and a plate full of empty oyster shells. The Catpenter’s face turns beet red in hatred of his former comrade, and his hammer is again produced, now intended as a lethal weapon. The nervous Walrus rises from the table, retrieves his walking cane, and cannot finish more of his favorite phrase than “The time has come!”, then crashes through the front door in a hasty stage of retreat. The camera follows as the Carpenter pursues the Walrus at furious pace all the way back up the coast, hammer madly swinging, while the sun and moon morph back into Tweedle Dum and Tweedle Dee in time for them to conclude, “The End”. The story treatment elements fashioned by the Disney writers to embellish the original rhyme add zest and life to the characters and the tale, and certainly demonstrate more thought, planning, and effort in presentation than most competing versions of this story from other studios have ever approached.

Popeye’s Pappy (Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 1/25/52 – I. Sparber, dir.) – Poopdeck Pappy’s first appearance in Technicolor, after approximately a decade of hiatus. He is voiced somewhat differently than Mercer’s usual read, Mercer tossing in a higher pitch that resembles some elements of his voicingA noya for Popeye’s nephews. A notable revelation from this episode is that longevity seems to run in Popeye’s bloodline from both sides of the family, as we meet, for perhaps the only time in cartoon history, Popeye’s mother, who has still survived, even though we know as of 1940’s “Poopdeck Pappy” that pop was 99 years old. Two parents, presumably now over 100 years of age? It’s no wonder that Popeye himself was still standing when the Martian cosmic ager aged him to 125 years, in “Popeye, the Ace of Space” (1953).

Popeye’s Pappy (Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 1/25/52 – I. Sparber, dir.) – Poopdeck Pappy’s first appearance in Technicolor, after approximately a decade of hiatus. He is voiced somewhat differently than Mercer’s usual read, Mercer tossing in a higher pitch that resembles some elements of his voicingA noya for Popeye’s nephews. A notable revelation from this episode is that longevity seems to run in Popeye’s bloodline from both sides of the family, as we meet, for perhaps the only time in cartoon history, Popeye’s mother, who has still survived, even though we know as of 1940’s “Poopdeck Pappy” that pop was 99 years old. Two parents, presumably now over 100 years of age? It’s no wonder that Popeye himself was still standing when the Martian cosmic ager aged him to 125 years, in “Popeye, the Ace of Space” (1953).

After all these years, Mom sends Popeye on a voyage to locate his errant father, who allegedly went out to get him some spinach, and never returned. Little seems to be provided to Popeye for clues excepting an old photograph, when Pappy’s beard was still black. Simply through his bare knowledge of the seven seas, Popeye inexplicably zeroes in on the location of a tropical island, where the photographed image of Pappy dissolves into a view of him in the present day, sitting on a throne under a sign reading “King Pappy”, as a tribe of dark-skinned natives bow to him with the chant, “King Pop. Rag Mop. Be-Bop.” (The middle reference refers to the title of song that was flooding the airwaves for a few seasons, originally recorded by Johnny Lee Wills on Bullet records, but popularized by a hit version by the Ames Brothers on Coral. The song was a favorite of Bob Clampett’s, and provided a recurring go-to musical number for Cecil the seasick sea serpent for over a decade.) How Pappy became a king is also unexplained – especially considering that his subjects are, as we will learn, not above resorting to cannibalism. Perhaps Pappy survived his initiation into the secret order of the Midnight Bath years ago, just as Popeye later did in “Pop-Pie A La Mode”, discussed earlier in these articles. At any rate, Pappy receives the royal treatment, being fanned by the island’s most attractive beauties, and fed fresh cocoanut milk by applying a nozzle to the nut and squirting it in Pappy’s mouth as if from a seltzer bottle. Enter Popeye, introducing himself as Pappy’s son, and stating his intention to bring Pappy home. “I hates relatives”, declares Pappy, repeating his feelings first declared in “Goonland” (1938). Pappy tells Popeye to shove off, but the determined sailor picks Pappy up bodily, and begins carrying him away upon his shoulder. “Put, me down, ya ugly lookin’ brat”, bellows Pappy. As Popeye passes a large rock, Pappy notices a constrictor snake sleeping in its shade. Grabbing the snake’s tail, Pappy makes a substitution of the snake as Popeye’s new passenger. The snake puts the squeeze on Popeye, but the sailor breathes some flames and fumes from his pipe into the snake’s mouth, which travels in a ball down the length of the snake’s insides, exploding its tail, and deflating the serpent into the helplessness of a wet noodle. An age-old gag is next revisited: when Popeye hauls off Pappy again along with his entire throne chair, Pappy kicks Popeye into an alligator-infested river. A Popeye sock turns the gator into alligator bags – again. His throne chair back in place, Pappy plays a ukelele, while the local beauties parade in hula dance formation before him. Pappy sings “Oh how I love this life. Who needs a wife? Girlies by the score. Who could ask for more?” A standout by conrast appears amoing the dancers – white skinned, with bare, bony shoulders and pugnacious jaw, dressed in a sarong and tutti-frutti basket hat. It is of course our sailor man in drag, wearing a wig of unknown origin. “You’re new around here”, reacts a surprised Pappy, who is drawn to the attractiveness of this new frail, and follows “her” down the beach. Popeye attempts to lead Pappy aboard his ship, but catches his sarong on a splinter of a nearby tree, revealing his sailor suit. Pappy flips the ship’s gangplank to tumble Popeye alone on board the ship, who comes up with the ship’s anchor caught in his jaw. “All children should stay home with their mothers”, grumbles Pappy. Popeye now sneaks up from begind, catching Pappy’s outfit on the end of a harpoon. Finally realizing he needs help, Pappy toots his pipe as a signal for reinforcements. A large native, wearing sergeant’s stripes tattooed on his arm, rallies the tribe’s warriors, who pin Popeye to a tree with a volley of spears.

After all these years, Mom sends Popeye on a voyage to locate his errant father, who allegedly went out to get him some spinach, and never returned. Little seems to be provided to Popeye for clues excepting an old photograph, when Pappy’s beard was still black. Simply through his bare knowledge of the seven seas, Popeye inexplicably zeroes in on the location of a tropical island, where the photographed image of Pappy dissolves into a view of him in the present day, sitting on a throne under a sign reading “King Pappy”, as a tribe of dark-skinned natives bow to him with the chant, “King Pop. Rag Mop. Be-Bop.” (The middle reference refers to the title of song that was flooding the airwaves for a few seasons, originally recorded by Johnny Lee Wills on Bullet records, but popularized by a hit version by the Ames Brothers on Coral. The song was a favorite of Bob Clampett’s, and provided a recurring go-to musical number for Cecil the seasick sea serpent for over a decade.) How Pappy became a king is also unexplained – especially considering that his subjects are, as we will learn, not above resorting to cannibalism. Perhaps Pappy survived his initiation into the secret order of the Midnight Bath years ago, just as Popeye later did in “Pop-Pie A La Mode”, discussed earlier in these articles. At any rate, Pappy receives the royal treatment, being fanned by the island’s most attractive beauties, and fed fresh cocoanut milk by applying a nozzle to the nut and squirting it in Pappy’s mouth as if from a seltzer bottle. Enter Popeye, introducing himself as Pappy’s son, and stating his intention to bring Pappy home. “I hates relatives”, declares Pappy, repeating his feelings first declared in “Goonland” (1938). Pappy tells Popeye to shove off, but the determined sailor picks Pappy up bodily, and begins carrying him away upon his shoulder. “Put, me down, ya ugly lookin’ brat”, bellows Pappy. As Popeye passes a large rock, Pappy notices a constrictor snake sleeping in its shade. Grabbing the snake’s tail, Pappy makes a substitution of the snake as Popeye’s new passenger. The snake puts the squeeze on Popeye, but the sailor breathes some flames and fumes from his pipe into the snake’s mouth, which travels in a ball down the length of the snake’s insides, exploding its tail, and deflating the serpent into the helplessness of a wet noodle. An age-old gag is next revisited: when Popeye hauls off Pappy again along with his entire throne chair, Pappy kicks Popeye into an alligator-infested river. A Popeye sock turns the gator into alligator bags – again. His throne chair back in place, Pappy plays a ukelele, while the local beauties parade in hula dance formation before him. Pappy sings “Oh how I love this life. Who needs a wife? Girlies by the score. Who could ask for more?” A standout by conrast appears amoing the dancers – white skinned, with bare, bony shoulders and pugnacious jaw, dressed in a sarong and tutti-frutti basket hat. It is of course our sailor man in drag, wearing a wig of unknown origin. “You’re new around here”, reacts a surprised Pappy, who is drawn to the attractiveness of this new frail, and follows “her” down the beach. Popeye attempts to lead Pappy aboard his ship, but catches his sarong on a splinter of a nearby tree, revealing his sailor suit. Pappy flips the ship’s gangplank to tumble Popeye alone on board the ship, who comes up with the ship’s anchor caught in his jaw. “All children should stay home with their mothers”, grumbles Pappy. Popeye now sneaks up from begind, catching Pappy’s outfit on the end of a harpoon. Finally realizing he needs help, Pappy toots his pipe as a signal for reinforcements. A large native, wearing sergeant’s stripes tattooed on his arm, rallies the tribe’s warriors, who pin Popeye to a tree with a volley of spears.

The next thing you know, Popeye is in a pot, swimming among a pool of cut vegetables. Without much in the way of explanation, Pappy, who it appears has maintained a tolerance over the years for the natives’ cannibal tastes, as long as he himself isn’t on the menu, starts to have second thoughts at turning over his son to the natives. “Oh my garsh. Me own flesh and blood.” The sergeant begins mixing the ingredients in the pot well, by inserting an outboard motor as a mixer. Pappy reaches breaking pont, delivering his son’s famouus catch phrase: “That’s all I can stand. I can’t stands no more.” He confronts the sergeant, who rebels and challenges Pappy’s authority, by flinging Pappy Into the trunk of a tree, compressing him like an accordion’s bellows. However, when Pappy came to the island, he apparently arrived well-provisioned, as he has built and fastened to the tree an emergency box as if for a fire extinguisher, containing a spinach can behind the glass. The spinach is downed, and Pappy’s muscle develops the image of an erupting volcano. Grabbing a vine, Pappy lets out a Tarzan yell, then swoops down on the village center, making away with Popeye and the entire cooking pot. Before he can untie his son, a first swarm of natives closes in. Pappy turns the pot sideways, and bowls it at the natives, scoring a strike. (Reused gag from “Popeye Meets Ali Baba’s 40 Thieves”). Another squad of natives approaches from the opposite direction. With no time to untie the ropes, Pappy merely pops from the spinach can a reainig mouthful of greens for Popeye, allowing his son to pop the ropes off himself. The two now stand together as an invincible two-man army to handle the attacking horde. Spears fly, but Popeye diverts each one off course with a fist blow, over to Pappy, who socks them into a banboo wall to form a pair of shelves at about shoulder height. Next come the natives themselves, whom Popeye again diverts with his socks over to Pappy, who pounds each of them toward the bamboo wall. They land in a neat row with arms outstretched over the shelves, twelve deep against the wall. When the rack is full, Pappy hangs a sign around the forward native’s neck as if selling clothing, reading “Cheaper by the Dozen”. Pappy finally consents to sail home with his son, joining in Popeye’s closing theme with the couplet, ‘I am very happy that I am your Pappy.”

The next thing you know, Popeye is in a pot, swimming among a pool of cut vegetables. Without much in the way of explanation, Pappy, who it appears has maintained a tolerance over the years for the natives’ cannibal tastes, as long as he himself isn’t on the menu, starts to have second thoughts at turning over his son to the natives. “Oh my garsh. Me own flesh and blood.” The sergeant begins mixing the ingredients in the pot well, by inserting an outboard motor as a mixer. Pappy reaches breaking pont, delivering his son’s famouus catch phrase: “That’s all I can stand. I can’t stands no more.” He confronts the sergeant, who rebels and challenges Pappy’s authority, by flinging Pappy Into the trunk of a tree, compressing him like an accordion’s bellows. However, when Pappy came to the island, he apparently arrived well-provisioned, as he has built and fastened to the tree an emergency box as if for a fire extinguisher, containing a spinach can behind the glass. The spinach is downed, and Pappy’s muscle develops the image of an erupting volcano. Grabbing a vine, Pappy lets out a Tarzan yell, then swoops down on the village center, making away with Popeye and the entire cooking pot. Before he can untie his son, a first swarm of natives closes in. Pappy turns the pot sideways, and bowls it at the natives, scoring a strike. (Reused gag from “Popeye Meets Ali Baba’s 40 Thieves”). Another squad of natives approaches from the opposite direction. With no time to untie the ropes, Pappy merely pops from the spinach can a reainig mouthful of greens for Popeye, allowing his son to pop the ropes off himself. The two now stand together as an invincible two-man army to handle the attacking horde. Spears fly, but Popeye diverts each one off course with a fist blow, over to Pappy, who socks them into a banboo wall to form a pair of shelves at about shoulder height. Next come the natives themselves, whom Popeye again diverts with his socks over to Pappy, who pounds each of them toward the bamboo wall. They land in a neat row with arms outstretched over the shelves, twelve deep against the wall. When the rack is full, Pappy hangs a sign around the forward native’s neck as if selling clothing, reading “Cheaper by the Dozen”. Pappy finally consents to sail home with his son, joining in Popeye’s closing theme with the couplet, ‘I am very happy that I am your Pappy.”

Hello Aloha (Disney/RKO, Goofy, 2/19/52 – Jack Kinney, dir.) – One of Kinney’s late “everyman” Goof episodes, with Goofy playing the role of harried George Geef in the workaday world. The film was also one in a series of episodes where a musical guest star was featured on soundtrack – in this case appropriately Harry Owens and his Orchestra, recording star for Decca and Capitol in the Hawaiian music vein, and a prolific composer in the field, including of the Academy-Award winning “Sweet Leilani”.

Hello Aloha (Disney/RKO, Goofy, 2/19/52 – Jack Kinney, dir.) – One of Kinney’s late “everyman” Goof episodes, with Goofy playing the role of harried George Geef in the workaday world. The film was also one in a series of episodes where a musical guest star was featured on soundtrack – in this case appropriately Harry Owens and his Orchestra, recording star for Decca and Capitol in the Hawaiian music vein, and a prolific composer in the field, including of the Academy-Award winning “Sweet Leilani”.

Goof’s life is run by the clock. He races through the crowded streets to work – of course, late. His boss berates him for even taking a minute off to grab a drink from the water cooler. The clock on the wall spins and spins, while Goof churns out a mountai of paperwork – and ultimately envisions himself trapped inside the clock face, with the hands’ pointer repeatedly jabbing Goof in the rear end. But like the call of the wild, the “voice of escape” is heard in chorus of friendly tropical voices, as Goof stares at a calendar photo of island splendor. Despite his boss’s screams, Goody walks in slow motion as if in a dream world, donning his hat and coat, and drifting out the exit, never to return. We follow the Goof, as the backgrounds transform to a dreamy blue sky, and his business suit fades away into a tourist’s light tan leisure outfit and striped shirt. Another background dissolve, and Goof is magically transported to the shore of a Hawaiian island, suitcase in hand, waving farewell to the departing ship which just landed him there. An islander happily places a flower lei around Goof’s neck, and Goof gets into the island spitit by abandoning his shoes forever to walk barefoot through the sand like one of the locals. The narrator describes the island as a place where “time stands still” – and Goof proves it, by tossing away his pocket watch, which busts its mainspring to the accompanying twang of a Hawaiaan guitar as the watch smashes on a rock.

With nature abundant around him, Goof goes native, and decides who needs money in such a bountiful place, where he can wheel a grocery cart fashioned of bamboo, grab bananas and exotic fruit off the trees, and even harvest fresh turtle eggs for morning breakfast. He thus tosses his wallet away, little noticing the clamor as islanders scramble in a fight cloud for its contents. One final vestige of civilization, however, comes back to haunt him, as a bottle drifts into the lagoon, inside which is a telegram from his boss, reading “You’re fired,” The island is well equipped for such situations, with a convenient writing desk placed among the palm trees, at which Goofy retaliates with a return message, “I quit!” It also features full postal amenities, as Goof stuffs the return message in another bottle and drops it into a bamboo mailbox, from which a rear hatch opens to gently deposit the bottle into the ocean for the outgoing tide. Now Goof settles down to the task of settling in. He builds a hut out of straw and palm fronds, forming its roof with a comb as if dividing hair into a part down the middle. Inside, he settles into a hammock for a good night’s sleep. A sudden rainstorm hits, and Goof’s hammock fills with water, which he takes in stride, treating the siriation like it was bath day, and scrubbing himself with a brush. Dawn breaks, and the sun once again focuses its rays upon Goofy’s shelter – which is far from waterproof, and shrinks in a matter of moments from a hut to a mere grass skirt around Goofy’s waist. Nothing, however, dampens the Goof’s spitits, and he appropriately dances the hula.

With nature abundant around him, Goof goes native, and decides who needs money in such a bountiful place, where he can wheel a grocery cart fashioned of bamboo, grab bananas and exotic fruit off the trees, and even harvest fresh turtle eggs for morning breakfast. He thus tosses his wallet away, little noticing the clamor as islanders scramble in a fight cloud for its contents. One final vestige of civilization, however, comes back to haunt him, as a bottle drifts into the lagoon, inside which is a telegram from his boss, reading “You’re fired,” The island is well equipped for such situations, with a convenient writing desk placed among the palm trees, at which Goofy retaliates with a return message, “I quit!” It also features full postal amenities, as Goof stuffs the return message in another bottle and drops it into a bamboo mailbox, from which a rear hatch opens to gently deposit the bottle into the ocean for the outgoing tide. Now Goof settles down to the task of settling in. He builds a hut out of straw and palm fronds, forming its roof with a comb as if dividing hair into a part down the middle. Inside, he settles into a hammock for a good night’s sleep. A sudden rainstorm hits, and Goof’s hammock fills with water, which he takes in stride, treating the siriation like it was bath day, and scrubbing himself with a brush. Dawn breaks, and the sun once again focuses its rays upon Goofy’s shelter – which is far from waterproof, and shrinks in a matter of moments from a hut to a mere grass skirt around Goofy’s waist. Nothing, however, dampens the Goof’s spitits, and he appropriately dances the hula.

Goofy finds the abundance of time to accomplish his life’s goals – at his own pace. As he slowly sways between the trees, nearly asleep in a hammock, he releases his long-stifled urge to paint by takung a single brush stroke at a time at an easel with his left hand, while alternating by writing his novel, pressing a single typewriter key at a time with his right hand. Falling off the hammock into his easel, the fresh paint from his picture spreads over his shirt, transforming it into a Hawaiian floral. But his main daily activity consists of attending the luau, where he feasts on shark fin soup (each bowl containing a swarm of miniature circling fins), cocianut milk (including certified stickers on the nuts reading “Grade A”), fresh breadfruit (literally growing in the form of loaves from the trees), and the soothing “elixir of the luau” – the Bromo Oofi. A polonesian maiden dances the hula for Goof – who keeps his eyes well placed on everything but the storytelling hands, which tell the tale of the coming of a great white god who is the only one who can appease angry Pele, the fire goddess. A lei is placed on Goofy’s head like a crown, and he is carried on the shoulders of the natives up the slope of a steaming volcano. The narrator informs us, “Geef knew the friendly natives wouldn’t throw him to the volcano – but they did.” “Aloha Hoooooey!” he screams as he falls into the crater. Mighty Pele is stilled, and the volcano ceases its flow of steam, as the sun again shines brightly on the little island. What of the Goof? He somehow manages to pull imself out of the crater, somewhat scalded and his clothes definitely the worse for wear, but still takes the whole affair in good-natured stride, wishing us, “Aloha, goodbye!”

Goofy finds the abundance of time to accomplish his life’s goals – at his own pace. As he slowly sways between the trees, nearly asleep in a hammock, he releases his long-stifled urge to paint by takung a single brush stroke at a time at an easel with his left hand, while alternating by writing his novel, pressing a single typewriter key at a time with his right hand. Falling off the hammock into his easel, the fresh paint from his picture spreads over his shirt, transforming it into a Hawaiian floral. But his main daily activity consists of attending the luau, where he feasts on shark fin soup (each bowl containing a swarm of miniature circling fins), cocianut milk (including certified stickers on the nuts reading “Grade A”), fresh breadfruit (literally growing in the form of loaves from the trees), and the soothing “elixir of the luau” – the Bromo Oofi. A polonesian maiden dances the hula for Goof – who keeps his eyes well placed on everything but the storytelling hands, which tell the tale of the coming of a great white god who is the only one who can appease angry Pele, the fire goddess. A lei is placed on Goofy’s head like a crown, and he is carried on the shoulders of the natives up the slope of a steaming volcano. The narrator informs us, “Geef knew the friendly natives wouldn’t throw him to the volcano – but they did.” “Aloha Hoooooey!” he screams as he falls into the crater. Mighty Pele is stilled, and the volcano ceases its flow of steam, as the sun again shines brightly on the little island. What of the Goof? He somehow manages to pull imself out of the crater, somewhat scalded and his clothes definitely the worse for wear, but still takes the whole affair in good-natured stride, wishing us, “Aloha, goodbye!”

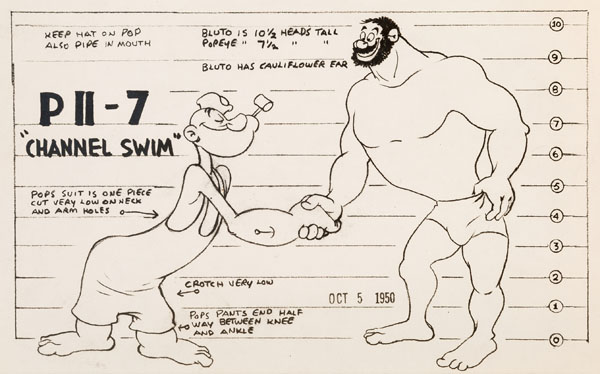

Swimmer Take All (Paramount/Popeye, 5/16/52 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.), takes us from one shore to another – as Popeye and Bluto engage in a channel swim from England to France. As usual, Bluto knows how to use every dirty trick in the book. First, as the starting gun fires, Bluto allows Popeye to dart ahead along the pier, then loosens a center board from the pier pilings, pushing d forward at the last second so that Popeye dives face-first into its end. As the sailor remains trapped in a hole in the board, Bluto uses Popeye as a diving board, and enters the channel. Olive, following Popeye’s progress in a rowboat, saws Popeye loose from the plank. Bluto meanwhile, thinking Popeye is out of the race, conserves his strength by floating on his back, gently paddling with his ear lobes. (A revised gag from “Beach Peach”.) “What’s a-matte, pal? Draggin’ yer anchor?”, quips Popeye, as he passes Bluto like a snail. Bluto quickly gets back into competition, passing Popeye without appearing to make any physical effort above water. “Look. No hands”, he taunts Popeye. The camera reveals how he can be propelled in this manner. Below the water’s surface, Bluto is riding atop a tall circus unicycle, which rolls along the ocean bottom. Bluto uses his freed hands to pull out a language book, trying to figure out how to say “Thanks for the loving cup” in French. Popeye puts on an extra burst of speed and passes him. Bluto retaliates by noting a loose thread on Popeye’s swimsuit. He gets hold of it and starts to unravel the suit’s shoulder. Tying the other end of the thread to a fish hook, Bluto tosses the hook into the sea, where a passing fish takes the bait (or was there any on that hook? The fish must be hungry if they’ll chomp down on empty steel.) Popeye suddenly looks down, and discovers he is nearly naked. ‘Oh, my garsh”, he shouts, and dives in the water to find the missing thread. To add to Popeye’s troubles, the little fish is swallowed by a giant one. Popeye produces knitting needles from nowhere, and begins reconstructing his suit. “Knit one, purl two. Pick up a sutch, that’s all ya do.” As he hauls in the thread, he pulls in the big fish, too, which opens it’s mouth to swallow Popeye. But a mighty sock from the sailor knocks the fish’s teeth out, allowing Popeye to escape.

On the surface, Bluto is now really taking it easy – aboard a wooden raft with sail, propelled by an electric fan with unknown portable power source never explained. “One side, blubberhead. You’re obstructing the sea lanes” shouts Popeye from behind. Bluto produces a can of sneexing powder, and blows some into Popeye’s nose. Popeye sneezes violently, and the strong breeze kicked up by it propels Bluto’s sail far ahead. Bluto repeats the process several times whenever the wind gives out, but on powdering #3, Popeye tries to hold back, turning his head in the opposite direction. When he still sneezes, he is propelled backwards, straight into Bluto’s raft, destroying it. Now Popeye appears to have a clear advantage, but Bluto swims underneath him, hooking to Popeye’s swimsuit a magnet. The magnet attracts a sunken magnetic mine left over from the war, which explodes upon making contact with the sailor. Popeye shoots our of the water, jet propelled backwards all the way to the starting line banner atop the English pier. Popeye get caught up in the banner, which stretches elastically, then propels Popeye forward again like a slingshot. Bluto watches aghast, as Popeye now passes his position, and lands where Olive is waiting, at a buoy making a spot one-half mile from the finish line. Out of his bottomless bag of tricks, Bluto produces an outboard motor strapped to his back, swamping Popeye in his wake. Popeye counters by revving up his pipe as a twirling propeller, closing in on Bluto. In a gag defying cartoon physics, Bluto passes a large vessel marked “Cement barge”, piled high with a load of cement – why isn’t this stuff already hardening where it stands? Instead, Bluto pulls a release latch on the side wall of the barge, allowing its contents to slip in a gooey lump into the sea, right upon Popeye., Now, amidst the water that you would think would also interfere with solidification, the cement hardens into a solid block, and sinks with Popeye entombed within into the ocean. All that remains extended out of the block to note Popeye’s presence is his pipe. This of course is enough in one of these cartoons, as Olive uses an air pump in her rowboat to propel spinach deep into the sea. Popeye detects its presence through his pipe, and sucks up the stuff, allowing for him to drill his way out of the encasement.

Without explanation as to where he gets the extra parts (particularly, roofing materials and glass windows), Popeye socks the cement block skyward, where its pieces assemble themselves into a lighthouse atop a channel island. Popeye then passes Bluto in a blur, washing the villain backwards into the door of the lighthouse. Bluto is revealed inside the windows of the upper floor of the structure, which becomes filled with water like a goldfish bowl. An additional passenger has ridden the same wave – a swordfish, which swims after Bluto in the confines of the lighthouse chamber, painfully scoring touchés with his nose upon Blito’s person. At the finish line, Popeye climbs a ladder up to the French pier, and proceeds forward to receive his loving cup – not realizing the thread of his suit has caught upon a nail on the ladder. With every step forward, the suit grows shorter and shorter – until the censorship standards require the scene to dissolve away. The final scene finds Olive rowing their return rowboat, her dialog giving every indication that se is no longer in a position of naivete about Popeye’s manly physique. “And in front of all those foreigners. I was never so embarrassed in all my life.” On the other end of the rowboat, Popeye, still appearing to be without his suit, is busy with the thread and knitting needles again, with his lower half hidden by sitting inside the loving cup. “But it was a close race, Olive”, he sums up. “I just barely won it.” (Knowing the fabled looser standards of the “French version” of many films of the day, one can only wonder, tongue in cheek, how much more such a version of this film might have revealed.)

The Simple Things (Disney/RKO, Mickey Mouse, 3/27/53 – Charles Nichols, dir.) – It is unknown if the writers and production staff on this film knew during the production that this would be the last entry in the “Mickey Mouse” series from the studio’s output of regular theatrical shorts. (The mouse would not star again on the big screen until 1983’s “Mickey’s Christmas Carol”.) Mickey’s series’ entries had already become quite sporadic, averaging one or two a year (including a gap in production when the nearly-completed “Plight of the Bumblebee” was scrapped), so it is unlikely the staff would have been easily tipped off to the demise of the series from any lapse in schedule, in view of the seeming absence of any mandatory production quota, relegating Mickey more to the realm of “special” appearances only. Still, if the staffers did realize this was the icon’s last go-round, they probably couldn’t have picked a more charming, and fitting, sendoff than this vehicle, which places the mouse at his leisure, in the type of activity that might befit a star about to go into semi-retirement and retreat from the hustle and bustle of tinseltown. Notably, this film would also mark the final big-screen appearance from the classic shorts of Pluto, with whose career Mickey’s had become indelibly intertwined in all the late installments of the series, including some films where the Mouse merely played second fiddle, with Pluto’s name emblazoned as the headliner. Pluto’s last star spotlight, however, had already passed a few episodes back (followed by an instance of indecision, where the poster department was informed that Pluto would be the star of “Pluto’s Christmas Tree” (1952), while final screen credits, now confirmed even in original RKO prints, gave the film to Mickey), so the Mouse would ultimately come out on top in the final competition for lead billing. The film is further memorable for a lilting theme tune, which oddly was not exploited in any known recorded version, nor to my knowledge as sheet music, yet has that Disney quality of forever etching itself into your head.

The Simple Things (Disney/RKO, Mickey Mouse, 3/27/53 – Charles Nichols, dir.) – It is unknown if the writers and production staff on this film knew during the production that this would be the last entry in the “Mickey Mouse” series from the studio’s output of regular theatrical shorts. (The mouse would not star again on the big screen until 1983’s “Mickey’s Christmas Carol”.) Mickey’s series’ entries had already become quite sporadic, averaging one or two a year (including a gap in production when the nearly-completed “Plight of the Bumblebee” was scrapped), so it is unlikely the staff would have been easily tipped off to the demise of the series from any lapse in schedule, in view of the seeming absence of any mandatory production quota, relegating Mickey more to the realm of “special” appearances only. Still, if the staffers did realize this was the icon’s last go-round, they probably couldn’t have picked a more charming, and fitting, sendoff than this vehicle, which places the mouse at his leisure, in the type of activity that might befit a star about to go into semi-retirement and retreat from the hustle and bustle of tinseltown. Notably, this film would also mark the final big-screen appearance from the classic shorts of Pluto, with whose career Mickey’s had become indelibly intertwined in all the late installments of the series, including some films where the Mouse merely played second fiddle, with Pluto’s name emblazoned as the headliner. Pluto’s last star spotlight, however, had already passed a few episodes back (followed by an instance of indecision, where the poster department was informed that Pluto would be the star of “Pluto’s Christmas Tree” (1952), while final screen credits, now confirmed even in original RKO prints, gave the film to Mickey), so the Mouse would ultimately come out on top in the final competition for lead billing. The film is further memorable for a lilting theme tune, which oddly was not exploited in any known recorded version, nor to my knowledge as sheet music, yet has that Disney quality of forever etching itself into your head.

All voices in the film are provided by Disney’s hand-picked successor at the mike. Jimmy MacDonald. Not only a convincing Mickey mimic, Macdonald had graduated to many other recurring voices in the Disney shorts (most notably, Pluto, and Chip of Chip ‘n’ Dale), as well as a feature role as Jaq the mouse in Cinderella, and several incidental supporting roles. Here, he adds to his repertoire the voice of a sassy seagull, which sounds a lot like an unspeeded Chip with an added tremolo to resemble a gull’s squalls. Macdonald would continue his voicing well after this final Mickey cartoon, providing recurring interstitials for the Disneyland and Wonderful World of Color shows, voice-overs for commercials in the American Motors series featuring Disney characters, record dates for Disneyland, Mickey Mouse Club, Mercury and RCA records, and voicings whenever needed for special purposes, such as Mattel talking phones or Show and Tell phonograph soundtracks for slides. He would also provide various dog yelps in the Pluto vein for the track of “101 Dalmatians” and possibly “Lady and the Tramp” – with this cartoon laying an interesting foundation for the voice work in the Dalmatian epic. For the only time known in the Pluto series, MacDonald’s yelps are oddly coupled with one genuine dog woof in one of the final shots of this cartoon. Disney would repeat the process with greater use in “Dalmatians”, with a higher percentage of real-life dog sounds, punctuated with MacDonald’s tracks for special emphasis and emotions not commonly found among real canines.

Our scene opens along a peaceful coastline, where waves lap gently against the shore, and a flock of gulls roosts atop a large reef. The gulls are disturbed from their slumber by two new arrivals – Mickey and Pluto. Mickey is wearing a fishing hat, and carrying rod and reel, a bag full of gear and a box lunch, plus a bait pail. Pluto is unfettered, and as usual exploring his new surroundings with his sniffer. Mickey sets himself up on a spot overlooking the water, atop a rocky ridge. Pluto continues to explore, and is so busy concentrating on the sensations picked up by his nose, he fails to watch where he is going, briefly dipping his face into a shallow shore pool, and coming up with a starfish as a passenger. The starfish sees what Pluto is next about to walk into, and hops out of the way, as Pluto bashes nose-first into a rock. The starfish disappears back into the shallows, but Pluto, still in a good mood, snorts it off casually, and proceeds on his way. Plito’s next discovery is a jet of water emitting from the sand. As Pluto looks down into one hole, another jet hits him from below the tail. Pluto swats at the sand from where it came, and pops from the earth a small clam. The clamshell opens to expose a face against a surface of pink crabmeat, which observes the dog, then slams shut. Pluto sniffs at the shell, but receives another spit of sea water, right into his eye. Pluto’s left eye opens with a puddle of water in its lower eyelid, and the black iris bobbing to the surface as if a floating dot. Pluto barks at the strange creature, but the clam opens and closes its shell as if barking right back. Pluto hops atop the shell to keep it shit, but the strong clam (who should probably qualify as a “muscle”), flips Pluto off his back, to fall upside down among the rocks. Now, the clam performs a corkscrew maneuver to burrow a tunnel into the sand, and comes up under Pluto’s tail, clamping tight upon the dog’s appendage. Pluto shrieks in pain, but can’t shake the little guy loose – his efforts to flip his tail only resulting in the appearance of using the clamshell as a yo yo. A twirl of his tail accidentally flips the clamshell into Pluto’s mouth, where the shell lodges firmly. Pluto’s tail comes loose as the clam opens to see what’s going on, but Pluto’s paws can’t get a grip on the object between his cheeks to pry the shell loose. Panicking, Pluto runs to Mickey for help.

Mickey has opened his lunch box, and is grabbing a few snacks before baiting his hook. Pluto enters, whining and hopping frantically. The clam, however, is so positioned in Pluto’s open mouth, that the pink interior crabmeat looks like a dead ringer for Pluto’s tongue, and bulges out in a beckoning fashion as if to cue Mickey that the dog wants something thrown in to eat. “Okay. Here ya’ go”, says Mickey, reaching into the lunch box for a sausage. The treat is flipped to Pluto, but clamped down on by the clam, who takes small bites to consume it in. Pluto desperately attempts to reach into his mouth with his paws, to prevent the clams’s free meal and object, “On, no, you don’y. This is mine.” All he gets for his trouble is a painful nip on the paws. The clam knows a good racket when it finds one, and signals like a tongue for more. Shifting Pluto’s snout with its body mass, the clam grabs away Mickey’s own sandwich, and devours that too – also delivering a watery spit into Mickey’s eye. Still the clam beckons for more. Fred Moore, who provides the last animation of Mickey, continues to develop the mouse’s personality with some new and surprising disgust takes, as a wary Mickey begins to wonder what’s gotten into this dog. He reaches into the lunch pail for a replacement sandwich for himself, and also takes out a pepper shaker for seasoning. Unfamiliar with this object, the clam grabs away the shaker, swallowing it down whole. It quickly develops an uncontrollable case of sneezes, sending disturbing-looking vibrations through helpless Pluto’s head with a springy guitar effect on soundtrack. Mickey laughs in spite of himself, at the trouble he thinks Pluto has caused himself by his greed, until another sneeze finally dislodges the clam from Pluto’s mouth, popping the shell into Mickey’s hand. In a nice and seemingly candid vocal read (possibly inspired by similar conversational interruptions for which Arthur Lake as Dagwood Bumstead was well known in the “Blondie” movie series), Mickey’s laughter abruptly changes to a perplexed, “Eh?”. A third sneezes blasts Mickey in the face, sending the clamshell onto the sands. Using its shell halves as legs, the clam scampers for the safety of the water, punctuated by repeated sneezes all along the way.

Mickey has opened his lunch box, and is grabbing a few snacks before baiting his hook. Pluto enters, whining and hopping frantically. The clam, however, is so positioned in Pluto’s open mouth, that the pink interior crabmeat looks like a dead ringer for Pluto’s tongue, and bulges out in a beckoning fashion as if to cue Mickey that the dog wants something thrown in to eat. “Okay. Here ya’ go”, says Mickey, reaching into the lunch box for a sausage. The treat is flipped to Pluto, but clamped down on by the clam, who takes small bites to consume it in. Pluto desperately attempts to reach into his mouth with his paws, to prevent the clams’s free meal and object, “On, no, you don’y. This is mine.” All he gets for his trouble is a painful nip on the paws. The clam knows a good racket when it finds one, and signals like a tongue for more. Shifting Pluto’s snout with its body mass, the clam grabs away Mickey’s own sandwich, and devours that too – also delivering a watery spit into Mickey’s eye. Still the clam beckons for more. Fred Moore, who provides the last animation of Mickey, continues to develop the mouse’s personality with some new and surprising disgust takes, as a wary Mickey begins to wonder what’s gotten into this dog. He reaches into the lunch pail for a replacement sandwich for himself, and also takes out a pepper shaker for seasoning. Unfamiliar with this object, the clam grabs away the shaker, swallowing it down whole. It quickly develops an uncontrollable case of sneezes, sending disturbing-looking vibrations through helpless Pluto’s head with a springy guitar effect on soundtrack. Mickey laughs in spite of himself, at the trouble he thinks Pluto has caused himself by his greed, until another sneeze finally dislodges the clam from Pluto’s mouth, popping the shell into Mickey’s hand. In a nice and seemingly candid vocal read (possibly inspired by similar conversational interruptions for which Arthur Lake as Dagwood Bumstead was well known in the “Blondie” movie series), Mickey’s laughter abruptly changes to a perplexed, “Eh?”. A third sneezes blasts Mickey in the face, sending the clamshell onto the sands. Using its shell halves as legs, the clam scampers for the safety of the water, punctuated by repeated sneezes all along the way.

En route to the sea, the clam attracts the attentions of one of the roosting seagulls. “Food”, the bird cries. The gull, however, is one step too late, as the clam dives into the ocean, leaving the gull with only a watery splash in the face from a final sneeze. Back at Mickey’s ledge, Mickey tries to make amends to his dog by offering him the last sausage. Who should swoop in but the scavenging seagull, to nab the treat away in mid-air before it reaches Pluto’s lips. “Too bad, pal”, Mickey sadly declares, showing Pluto that the lunch box is now empty. Pluto sniffs around to be sure that all food is gone, and dips his nose into the bait pail. The smell is too much for Pluto to even consider in the category of an edible, and he winces and shrivels up his nose in disdain for the pail’s contents. But another pair of eyes has sighted the pail with much more enthusiasm – the seagull. “Fresh fish!”, he squeals. He first focuses on what Mickey is baiting a hook with. As Mickey rears back his rod to make a cast, the gull literally walks upon air, with the mannerisms of attempting to catch a football forward pass. His beak chomps down on the bait, but Mickey’s casting arm lets loose with a powerfil flip, taking the hook and the seagull along with it. The gull winds up dipped into the ocean, crashing smack into one of the reefs and developing a large pink lump on his head (which the bird removes by forcibly compressing the growth back into his head between his wings), The gull returns to Mickey’s cliff, where Mickey is rebaiting the hook. The mouse has briefly removed his hat, but when noticing a circling gull, replaces it quickly back upon his brow. The gull lands atop it, unseen by the mouse, until the gull utters the words, “Let’s eat.” Mickey looks quickly around for the source of the voice, while the gull takes the opportunity to snatch the bait fish again while Mickey isn’t looking. Then, Mickey spies the telltale shadow silhouette in the water of the bird atop his hat. Removing the chapeau, Mickey confronts his adversary face to face for the first time. “Howdy”, chirps the gull, demonstrating his fearlessness in the situation.

En route to the sea, the clam attracts the attentions of one of the roosting seagulls. “Food”, the bird cries. The gull, however, is one step too late, as the clam dives into the ocean, leaving the gull with only a watery splash in the face from a final sneeze. Back at Mickey’s ledge, Mickey tries to make amends to his dog by offering him the last sausage. Who should swoop in but the scavenging seagull, to nab the treat away in mid-air before it reaches Pluto’s lips. “Too bad, pal”, Mickey sadly declares, showing Pluto that the lunch box is now empty. Pluto sniffs around to be sure that all food is gone, and dips his nose into the bait pail. The smell is too much for Pluto to even consider in the category of an edible, and he winces and shrivels up his nose in disdain for the pail’s contents. But another pair of eyes has sighted the pail with much more enthusiasm – the seagull. “Fresh fish!”, he squeals. He first focuses on what Mickey is baiting a hook with. As Mickey rears back his rod to make a cast, the gull literally walks upon air, with the mannerisms of attempting to catch a football forward pass. His beak chomps down on the bait, but Mickey’s casting arm lets loose with a powerfil flip, taking the hook and the seagull along with it. The gull winds up dipped into the ocean, crashing smack into one of the reefs and developing a large pink lump on his head (which the bird removes by forcibly compressing the growth back into his head between his wings), The gull returns to Mickey’s cliff, where Mickey is rebaiting the hook. The mouse has briefly removed his hat, but when noticing a circling gull, replaces it quickly back upon his brow. The gull lands atop it, unseen by the mouse, until the gull utters the words, “Let’s eat.” Mickey looks quickly around for the source of the voice, while the gull takes the opportunity to snatch the bait fish again while Mickey isn’t looking. Then, Mickey spies the telltale shadow silhouette in the water of the bird atop his hat. Removing the chapeau, Mickey confronts his adversary face to face for the first time. “Howdy”, chirps the gull, demonstrating his fearlessness in the situation.