The apartment I lived in above my dad’s garage was 520 square feet. Newly returned from Ireland after eight weeks of shooting my first movie, Circle of Friends, I sat on the small sofa and stared at my huge suitcases. There were so many of them. What had I packed for—a roaring social life after filming for 12 hours a day in a small village in southeastern Ireland? The village did have a diverse ratio of post-work activities, with nine pubs, two churches, and a grocery store (that was also the post office), but that shop closed at 4 pm.

I had purchased quite a lot of sweaters. Everybody’s auntie or granny or hard-up friend (“Sure he left her with the four children after robbing all their piggy banks and moving in with some floozy, bogtrotter from Clonown”) knitted sweaters for cash. They saw me coming: chapped lips, chilly, purple knuckles, and a sizable bosom that they might have seen as their spiritual duty to help conceal. Their sweaters kept me nice for God.

I’m not sure what I had expected upon my return. Phones ringing off the hook, I suppose, thick ivory cards on top of my nonexistent fireplace inviting me to parties in Cannes. Barely having time to unpack all my Aran sweaters before heading off to do another movie with a handsome, floppy-haired actor like Hugh Grant, if not the actual Hugh Grant.

One leading role in a movie and I thought the shape of life would suddenly look different. How could all of that excitement, all of that adventure and creativity not have conga-lined its way off the set and into my real life. Jesus, I thought, wanting to do this job is insane.

You don’t just have to win the lottery, you have to keep winning it again and again and again, and who the fuck is going to have that much luck?

The ten grand I’d been paid for Circle of Friends had seen off the mountainous debt I’d accrued. It also bought four new tires for the Ford Fiesta, which at this point was more piñata than party: the aftermath of a Fiesta, a mechanical hangover on wheels. I’d loaned the car to Isla while I’d been gone, and I think she might have actually lived in it and thrown some memorable parties.

The suitcases loomed like relics, monuments of a recent past, their semicircle giving off serious Druid vibes, reminding me I was in need of a soothsayer.

I called my agent.

“Ah, you’re back,” she said cheerfully. “Great. I expect you’d like a nice rest.”

“No, not really. I’d quite like another job, actually.”

“Ah, yes. Well, I’ll definitely call you if anything like that comes up.”

“Is there anything on the horizon?”

“Oh well, there’s always something on the horizon—though who knows how close it will actually get.”

“Well, you will presumably?”

“Yes, fingers crossed.”

We hung up. I thought that if the soothsayer in my life was crossing fingers and that I was a lottery winner who needed to win again, then I should probably just tuck in, here on my Easter Island sofa with my Moai suitcases and wait for the future to happen.

The phone rang.

“Ah!” It was my agent again. “You must have magical powers.”

I looked at my suitcases.

“They want to see you for a commercial tomorrow, don’t think it’s a very good commercial and hardly any money even if you did get it, but it’s an audition, and you’re great at those, so onward and upward. I’ll call you back with the address.”

My suitcases shrugged their luggage tags as she hung up—an audition is not a job and a commercial is not a film, but hey!

“There are no small parts, only small actors,” said someone brilliant like Maggie Smith or Stanislavsky. “I am good at auditions,” I said triumphantly, standing up from the sofa. “I shall go to that audition, and I shall get that shitty job!”

I called Isla. “We are going to the pub to celebrate!”

“Oooo, what are we celebrating?”

“Mediocrity, but on a grand scale.”

“I will dress appropriately,” she said solemnly.

You don’t just have to win the lottery, you have to keep winning it again and again and again, and who the fuck is going to have that much luck?Two days later I hurried down Brewer Street in Soho, found the casting office for the audition, and signed my name on the clipboard in the anteroom. The room was already filled with girls. There’s a strange feeling when you walk into a casting call full of actresses, everyone’s nice, but it’s slightly serrated.

Each girl was in her best pick-me! outfit but there were a few subcategories of approach in general. Some had already given up, having noted that the girl sitting next to them had gotten the last three jobs they had both gone up for. Some appeared to be completely disinterested in the whole process and indicated that they had much loftier things to be getting on with: another script that they must busily highlight, a loud inquiry to the casting assistant about how long this might take as there were four more auditions to get to that morning. The smiley chatterbox who asked you where you’d bought every single thing you were wearing and interspersed question with an “I’m never gonna get this.” The steel in her eyes, though, said she actually thought she might.

Eventually my name was called, and I was ushered into a large room with more people in it than I had expected. Usually at a casting, it’s the casting director, an assistant operating the camera, and sometimes the director. This room was filled with almost two rows of chairs in a wide semicircle, every seat taken by a man in a suit, mostly with their jackets over the back of the chair and their ties loosened. A stool stood in front of the semicircle and next to it was a tall receptacle, like you see next to the sofas in a hotel lobby, you know, an ashtray, but it was filled with pieces of chocolate.

“Okay, lovey,” said the bored director, “pop your coat off and just leave it on the floor as we’ve run out of chairs. These gentlemen seated behind me are from the ad agency, and I’m Martin, your director.” He half bowed with a wan flourish.

“Have a seat,” he said, gesturing to the stool.

“Is that an ashtray?” I asked, pointing to the tall receptacle filled with chocolates.

“Not currently.”

There had been no script provided, so I wondered what exactly they needed me to do.

“Okay, so what we’re selling today is chocolate. You’ve seen the movie When Harry Met Sally?

“Yes.”

“You know the scene where she fakes an orgasm?”

“Yes.”

“Okay. Eat a piece of chocolate and do that.”

“Fake an orgasm?”

“Yes. Unless you fancy having a real one.” He chuckled odiously. The 17 ad executives leaned slightly forward in their chairs.

“I’ll need you to do it twice, once just normally, then make the second one bigger—that’ll be used for the Netherlands market.” I tried to digest this information.

“Um, do the Dutch really—”

“Look, just get on with it, will you, lovey? Tick-tock, et cetera.”

I thought about all the girls waiting outside. All of us vying for an opportunity that was actually humiliation dressed up in a pick-me! outfit. I wanted to run out there and warn them. I wanted to tell them we were better than this, better than being lunchtime entertainment for a bunch of pervy execs, their perviness sanctioned by this being considered “work.” But of course I didn’t, because the fire was lit and it required fuel, and any fuel, however troubling, will burn just the same.

The chocolate was revolting, a feat of cocoa avoidance and ersatz sugar.

“Mmmm… mmmm, mmmm,” I said, throwing my head around like Meg Ryan in Katz’s Deli. I attempted her cries of “YES! YES! YES!”

“NYESH! NYESH! NYESH!” I gurgled, on account of the gumming agent used in the chocolate.

“That’s it, “said Martin Scorsleazy, “really show us what that chocolate can do for you.”

Beyond gagging, there was not much. I attempted a few more groans and seizures and then, realizing there was nowhere to spit out the chocolate, I did what so many women do in the name of pleasing men, and I swallowed.

I wanted to tell them we were better than this, better than being lunchtime entertainment for a bunch of pervy execs, their perviness sanctioned by this being considered “work.”“Okay, lovely, that was indeed lovely. Now let’s see it again but remember this time do it bigger for the Dutch.” I swiped my tongue across my teeth, trying to remove the vestiges of chocolate, to accommodate round two. The chocolate had shellacked my teeth with a hard, sweet, presumably brown finish.

“I don’t think I can do it again,” I said. The room snickered as one.

“Course you can, love, that’s the best bit about being a girl!” came a voice from the ad-men cabal.

I tried to keep my lips over my teeth as I began to speak but then realized the audience actually deserved to see what they were promoting. My ambitious fire, that needed fuel, would have to go unfed.

“No, what I meant to say was I won’t do it again because I will throw up.” They thought I was talking about the chocolate, but it was really my shame at having gone along with the whole grotesquery. And the fucking chocolate.

Scorsleazy sneered and rolled his eyes. “Well, all of the other girls have apparently very much enjoyed this.” I gathered the good coat I’d worn off the floor, smiled mightily, and said, “They were faking it.”

__________________________________

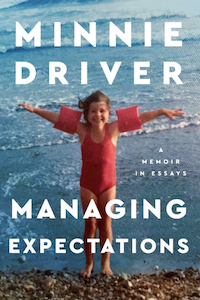

Excerpt from Managing Expectations: A Memoir in Essays by Minnie Driver. Published by HarperOne. Copyright © 2022 HarperCollins.